I Lost Faith I Ngods Existence but Found It Again

Tomorrow'southward Gods: What is the future of religion?

(Image credit:

Getty Images

)

Throughout history, people's faith and their attachments to religious institutions take transformed, argues Sumit Paul-Choudhury. So what's next?

Before Mohammed, before Jesus, before Buddha, in that location was Zoroaster. Some 3,500 years agone, in Bronze Historic period Iran, he had a vision of the one supreme God. A 1000 years after, Zoroastrianism, the world'due south first groovy monotheistic religion, was the official faith of the mighty Farsi Empire, its burn down temples attended by millions of adherents. A thousand years after that, the empire complanate, and the followers of Zoroaster were persecuted and converted to the new faith of their conquerors, Islam.

Another 1,500 years later – today – Zoroastrianism is a dying religion, its sacred flames tended by always fewer worshippers.

We take it for granted that religions are born, abound and die – simply we are also oddly bullheaded to that reality. When someone tries to start a new religion, it is frequently dismissed equally a cult. When we recognise a religion, we treat its teachings and traditions equally timeless and sacrosanct. And when a religion dies, it becomes a myth, and its claim to sacred truth expires. Tales of the Egyptian, Greek and Norse pantheons are now considered legends, not holy writ.

Even today'due south dominant religions accept continually evolved throughout history. Early on Christianity, for case, was a truly wide church: ancient documents include yarns well-nigh Jesus' family life and testaments to the nobility of Judas. It took three centuries for the Christian church to consolidate around a canon of scriptures – and and so in 1054 information technology split into the Eastern Orthodox and Catholic churches. Since so, Christianity has connected both to grow and to splinter into ever more than disparate groups, from silent Quakers to snake-handling Pentecostalists.

You might also similar:

• How and why did religion evolve?

• Practise humans have a faith instinct?

• How long can civilisation survive?

If you believe your faith has arrived at ultimate truth, yous might reject the idea that it will change at all. But if history is any guide, no matter how securely held our beliefs may be today, they are likely in fourth dimension to be transformed or transferred as they pass to our descendants – or simply to fade away.

If religions have inverse so dramatically in the past, how might they modify in the hereafter? Is in that location any substance to the claim that conventionalities in gods and deities will die out birthday? And as our civilisation and its technologies become increasingly complex, could entirely new forms of worship emerge? (Find out what information technology would mean if AI adult a "soul".)

A flame burns in a Zoroastrian Burn Temple, possibly for more than a millennium (Credit: Getty Images)

To respond these questions, a good starting point is to enquire: why do we take religion in the beginning identify?

Reason to believe

Ane notorious respond comes from Voltaire, the 18th Century French polymath, who wrote: "If God did not exist, it would be necessary to invent him."Because Voltaire was a trenchant critic of organised faith, this quip is often quoted cynically. But in fact, he was being perfectly sincere. He was arguing that conventionalities in God is necessary for society to function, even if he didn't approve of the monopoly the church building held over that belief.

Many mod students of organized religion agree. The wide thought that a shared faith serves the needs of a society is known every bit the functionalist view of religion. There are many functionalist hypotheses, from the thought that religion is the "opium of the masses", used by the powerful to command the poor, to the proposal that faith supports the abstruse intellectualism required for science and law. 1 recurring theme is social cohesion: religion brings together a community, who might and then form a hunting party, raise a temple or back up a party.

Those faiths that suffer are "the long-term products of extraordinarily circuitous cultural pressures, option processes, and development", writes Connor Wood of the Middle for Listen and Culture in Boston, Massachusetts on the religious reference website Patheos, where he blogs about the scientific study of faith. New religious movements are born all the time, but about don't survive long. They must compete with other faiths for followers and survive potentially hostile social and political environments.

Under this argument, whatsoever religion that does endure has to offer its adherents tangible benefits. Christianity, for example, was simply one of many religious movements that came and mostly went during the form of the Roman Empire. According to Wood, it was prepare apart by its ethos of caring for the ill – meaning more Christians survived outbreaks of disease than pagan Romans. Islam, too, initially attracted followers past emphasising honor, humility and charity – qualities which were not endemic in turbulent 7th-Century Arabia. (Read virtually the "lite triad" traits that can brand you a good person.)

Given this, we might expect the course that religion takes to follow the function it plays in a particular society – or equally Voltaire might have put it, that different societies will invent the particular gods they need. Conversely, we might wait similar societies to accept similar religions, fifty-fifty if they accept adult in isolation. And at that place is some evidence for that – although when it comes to religion, there are ever exceptions to any rule.

Belief in "Big Gods" immune the germination of societies made upwardly of strangers (Credit: Getty Images)

Hunter-gatherers, for case, tend to believe that all objects – whether animal, vegetable or mineral – have supernatural aspects (animism) and that the world is imbued with supernatural forces (animatism). These must be understood and respected; human morality more often than not doesn't effigy significantly. This worldview makes sense for groups too modest to demand abstruse codes of conduct, simply who must know their environment intimately. (An exception: Shinto, an ancient animist religion, is still widely practised in hyper-modern Japan.)

At the other stop of the spectrum, the teeming societies of the West are at least nominally faithful to religions in which a single watchful, anointed god lays down, and sometimes enforces, moral instructions: Yahweh, Christ and Allah. The psychologist Ara Norenzayan argues information technology was belief in these "Big Gods" that immune the formation of societies made up of large numbers of strangers. Whether that belief constitutes cause or outcome has recently been disputed, but the upshot is that sharing a organized religion allows people to co-exist (relatively) peacefully. The knowledge that Big God is watching makes certain we behave ourselves.

Or at least, it did. Today, many of our societies are huge and multicultural: adherents of many faiths co-exist with each other – and with a growing number of people who say they have no religion at all. Nosotros obey laws made and enforced past governments, not by God. Secularism is on the ascension, with scientific discipline providing tools to sympathise and shape the earth.

Given all that, there'southward a growing consensus that the futurity of faith is that information technology has no future.

Imagine there'south no sky

Powerful intellectual and political currents have driven this proffer since the early on 20th Century. Sociologists argued that the march of scientific discipline was leading to the "disenchantment" of club: supernatural answers to the large questions were no longer felt to be needed. Communist states like Soviet Russia and China adopted atheism equally state policy and frowned on even private religious expression. In 1968, the eminent sociologist Peter Berger told the New York Times that by "the 21st Century, religious believers are likely to be constitute only in small sects, huddled together to resist a worldwide secular culture".

Now that we're actually in the 21st Century, Berger'due south view remains an article of organized religion for many secularists – although Berger himself recanted in the 1990s. His successors are emboldened by surveys showing that in many countries, increasing numbers of people are saying they have no religion. That's most true in rich, stable countries like Sweden and Nihon, simply likewise, perhaps more than surprisingly, in places similar Latin America and the Arab globe. Even in the US, long a conspicuous exception to the axiom that richer countries are more secular, the number of "nones" has been ascension sharply. In the 2018 Full general Social Survey of Usa attitudes, "no faith" became the single largest group, edging out evangelical Christians.

Despite this, organized religion is not disappearing on a global calibration – at least in terms of numbers. In 2015, the Pew Research Center modelled the time to come of the world's slap-up religions based on demographics, migration and conversion. Far from a precipitous pass up in religiosity, it predicted a pocket-sized increase in believers, from 84% of the globe's population today to 87% in 2050. Muslims would abound in number to lucifer Christians, while the number unaffiliated with any religion would decline slightly.

Modern societies are multicultural where followers of many different faiths live side by side (Credit: Getty Images)

We likewise need to be careful when interpreting what people mean past "no religion". "Nones" may exist disinterested in organised faith, but that doesn't mean they are militantly atheist. In 1994, the sociologist Grace Davie classified people according to whether they belonged to a religious group and/or believed in a religious position. The traditionally religious both belonged and believed; hardcore atheists did neither. Then in that location are those who belong but don't believe – parents attention church to go a place for their kid at a faith school, perhaps. And, finally, there are those who believe in something, but don't vest to any group.

The inquiry suggests that the concluding two groups are significant. The Understanding Unbelief project at the University of Kent in the Uk is conducting a three-year, six-nation survey of attitudes among those who say they don't believe God exists ("atheists") and those who don't think it's possible to know if God exists ("agnostics"). In interim results released in May 2019, the researchers constitute that few unbelievers actually place themselves by these labels, with significant minorities opting for a religious identity.

What's more, effectually three-quarters of atheists and nine out of x agnostics are open to the being of supernatural phenomena, including everything from astrology to supernatural beings and life after death. Unbelievers "exhibit significant multifariousness both within, and between, unlike countries.

Accordingly, at that place are very many ways of being an unbeliever", the report ended – including, notably, the dating-website platitude "spiritual, but not religious". Like many cliches, it'south rooted in truth. Only what does it actually mean?

The old gods return

In 2005, Linda Woodhead wrote The Spiritual Revolution, in which she described an intensive study of conventionalities in the British town of Kendal. Woodhead and her co-author found that people were apace turning away from organised religion, with its accent on fitting into an established club of things, towards practices designed to accentuate and foster individuals' ain sense of who they are. If the boondocks'southward Christian churches did not cover this shift, they concluded, congregations would dwindle into irrelevance while cocky-guided practices would become the mainstream in a "spiritual revolution".

Today, Woodhead says that revolution has taken place – and non but in Kendal. Organised organized religion is waning in the Britain, with no real end in sight. "Religions do well, and always have done, when they are subjectively convincing – when you have the sense that God is working for you lot," says Woodhead, now professor of folklore of religion at the University of Lancaster in the Great britain.

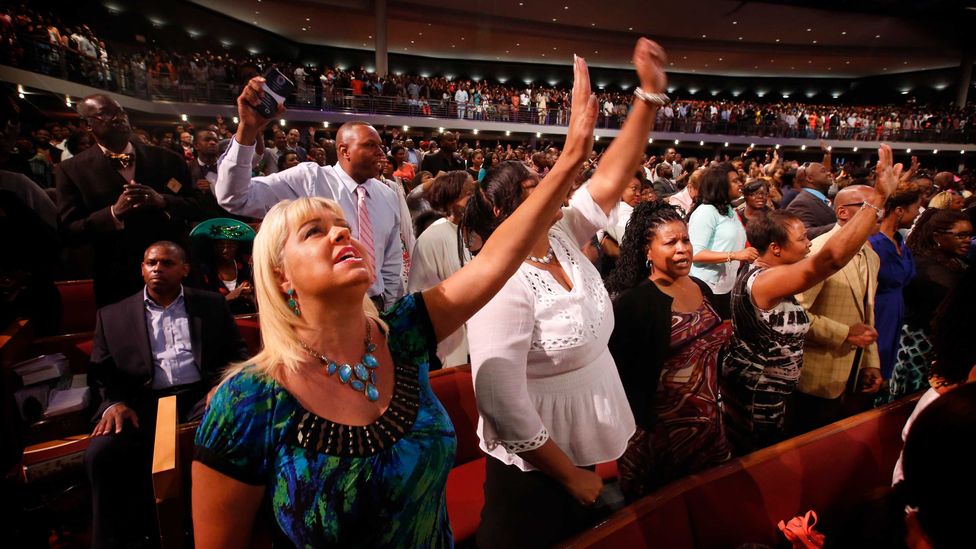

U.s. megachurches bring in thousands of worshippers (Credit: Getty Images)

In poorer societies, you might pray for good fortune or a stable job. The "prosperity gospel" is fundamental to several of America's megachurches, whose congregations are often dominated by economically insecure congregations. But if your bones needs are well catered for, you are more likely to be seeking fulfilment and significant. Traditional faith is failing to deliver on this, especially where doctrine clashes with moral convictions that arise from secular society – on gender equality, say.

In response, people have started constructing faiths of their own.

What do these cocky-directed religions look like? One arroyo is syncretism, the "option and mix" arroyo of combining traditions and practices that often results from the mixing of cultures. Many religions have syncretistic elements, although over fourth dimension they are alloyed and become unremarkable. Festivals similar Christmas and Easter, for example, have archaic pagan elements, while daily practice for many people in China involves a mixture of Mahayana Buddhism, Taoism and Confucianism. The joins are easier to see in relatively young religions, such equally Vodoun or Rastafarianism.

An alternative is to streamline. New religious movements often seek to preserve the cardinal tenets of an older religion while stripping it of trappings that may accept become stifling or old-fashioned. In the West, one form this takes is for humanists to rework religious motifs: there have been attempts to rewrite the Bible without any supernatural elements, calls for the construction of "atheist temples" defended to contemplation. And the "Sunday Assembly" aims to recreate the atmosphere of a lively church service without reference to God. But without the deep roots of traditional religions, these can struggle: the Sunday Assembly, after initial rapid expansion, is at present reportedly struggling to keep upwards its momentum.

But Woodhead thinks the religions that might sally from the current turmoil will accept much deeper roots. The beginning generation of spiritual revolutionaries, coming of age in the 1960s and 1970s, were optimistic and universalist in outlook, happy to accept inspiration from faiths around the world. Their grandchildren, however, are growing upwardly in a globe of geopolitical stresses and socioeconomic angst; they are more likely to hark back to supposedly simpler times. "At that place is a pull abroad from global universality to local identities," says Woodhead.

DEEP Culture

This commodity is part of a BBC Future series about the long view of humanity, which aims to stand up back from the daily news cycle and widen the lens of our current place in time.

Modern society is suffering from "temporal exhaustion", the sociologist Elise Boulding once said. "If 1 is mentally out of breath all the fourth dimension from dealing with the nowadays, there is no energy left for imagining the time to come," she wrote.

That's why the Deep Civilisation season is exploring what really matters in the broader arc of human history and what it means for usa and our descendants.

"It's really important that they're your gods, they weren't merely made upward."

In the European context, this sets the phase for a resurgence of involvement in paganism. Reinventing half-forgotten "native" traditions allows the expression of modern concerns while retaining the patina of age. Paganism also oft features divinities that are more than like diffuse forces than anthropomorphic gods; that allows people to focus on issues they feel sympathetic towards without having to make a leap of organized religion to supernatural deities.

In Iceland, for example, the pocket-size merely fast-growing Ásatrú faith has no particular doctrine beyond somewhat curvation celebrations of Onetime Norse customs and mythology, but has been agile on social and ecological problems. Similar movements be across Europe, such as Druidry in the UK. Not all are liberally inclined. Some are motivated by a desire to render to what they see as bourgeois "traditional" values – leading in some cases to clashes over the validity of opposing behavior.

These are niche activities at the moment, and might sometimes exist more about playing with symbolism than heartfelt spiritual exercise. But over fourth dimension, they canevolve into more heartfelt and coherent conventionalities systems: Woodhead points to the robust adoption of Rodnovery – an often conservative and patriarchal pagan religion based around the reconstructed behavior and traditions of the aboriginal Slavs – in the former Soviet Union as a potential exemplar of things to come.

A adult female dances as druids, pagans and revellers assemble at Stonehenge (Credit: Getty Images)

And then the nones mostly stand for non atheists, nor even secularists, only a mixture of "apatheists" – people who but don't care near organized religion – and practitioners of what y'all might call "disorganised organized religion". While the world religions are probable to persist and evolve for the foreseeable time to come, we might for the rest of this century see an efflorescence of relatively small religions jostling to break out among these groups. But if Big Gods and shared faiths are primal to social cohesion, what happens without them?

One nation nether Mammon

1 reply, of course, is that we only go on with our lives. Munificent economies, expert government, solid educational activity and effective rule of law can ensure that we rub forth happily without any kind of religious framework. And indeed, some of the societies with the highest proportions of non-believers are amid the virtually secure and harmonious on Earth.

What remains debatable, however, is whether they tin can afford to be irreligious considering they have strong secular institutions – or whether being secular has helped them reach social stability. Religionists say even secular institutions accept religious roots: civil legal systems, for example, codify ideas near justice based on social norms established by religions. The likes of the New Atheists, on the other hand, argue that religion amounts to little more than superstition, and abandoning it will enable societies to ameliorate their lot more effectively.

Connor Wood is not so certain. He contends that a potent, stable society like Sweden's is both extremely complex and very expensive to run in terms of labour, money and energy – and that might non be sustainable even in the brusque term. "I call up it'south pretty articulate that we're inbound into a menses of not-linear modify in social systems," he says. "The Western consensus on a combination of market capitalism and democracy tin't exist taken for granted."

That'southward a problem, since that combination has radically transformed the social environment from the one in which the globe religions evolved – and has to some extent supplanted them.

"I'd be careful about calling capitalism a organized religion, but a lot of its institutions have religious elements, as in all spheres of homo institutional life," says Wood. "The 'invisible hand' of the market nigh seems similar a supernatural entity."

Financial exchanges, where people meet to deport highly ritualised trading activity, seem quite like temples to Mammon, too. In fact, religions, even the defunct ones, tin provide uncannily appropriate metaphors for many of the more intractable features of modern life.

A Roman Catholic priest officiates mass on the first day of trading at the Philippine Stock Exchange in Manila (Credit: Getty Images)

The pseudo-religious social order might work well when times are adept. Merely when the social contract becomes stressed – through identity politics, culture wars or economic instability – Woods suggests the effect is what we see today: the rise of authoritarians in country afterward country. He cites enquiry showing that people ignore authoritarian pitches until they sense a deterioration of social norms.

"This is the human beast looking around and saying we don't agree how we should behave," Wood says. "And we need authority to tell u.s.." Information technology's suggestive that political strongmen are often hand in glove with religious fundamentalists: Hindu nationalists in India, say, or Christian evangelicals in the United states of america. That's a potent combination for believers and an unsettling one for secularists: can annihilation span the gap between them?

Mind the gap

Perhaps 1 of the major religions might change its form plenty to win dorsum not-believers in significant numbers. In that location is precedent for this: in the 1700s, Christianity was ailing in the US, having go dull and formal even equally the Age of Reason saw secular rationalism in the ascendant. A new baby-sit of travelling fire-and-brimstone preachers successfully reinvigorated the faith, setting the tone for centuries to come – an effect called the "Dandy Awakenings".

The parallels with today are easy to draw, but Woodhead is sceptical that Christianity or other earth religions can make up the ground they accept lost, in the long term. Once the founders of libraries and universities, they are no longer the fundamental sponsors of intellectual thought. Social change undermines religions which don't adjust it: earlier this twelvemonth, Pope Francis warned that if the Cosmic Church didn't acknowledge its history of male person domination and sexual abuse it risked becoming "a museum". And their trend to claim we sit at the pinnacle of creation is undermined past a growing sense that humans are not so very significant in the grand scheme of things.

Perhaps a new religion will emerge to fill the void? Over again, Woodhead is sceptical. "Historically, what makes religions rise or fall is political support," she says, "and all religions are transient unless they get imperial support." Zoroastrianism benefited from its adoption by the successive Persian dynasties; the turning bespeak for Christianity came when it was adopted by the Roman Empire. In the secular West, such support is unlikely to be forthcoming, with the possible exception of the Usa. In Russia, by dissimilarity, the nationalistic overtones of both Rodnovery and the Orthodox church wins them tacit political bankroll.

Only today, there's another possible source of support: the internet.

Online movements gain followers at rates unimaginable in the past. The Silicon Valley mantra of "motion fast and break things" has go a self-evident truth for many technologists and plutocrats. #MeToo started out as a hashtag expressing anger and solidarity but now stands for real changes to long-standing social norms. And Extinction Rebellion has striven, with considerable success, to trigger a radical shift in attitudes to the crises in climate change and biodiversity.

None of these are religions, of course, but they exercise share parallels with nascent belief systems – peculiarly that key functionalist objective of fostering a sense of community and shared purpose. Some take confessional and sacrificial elements, too. So, given fourth dimension and motivation, could something more explicitly religious abound out of an online customs? What new forms of organized religion might these online "congregations" come upwards with?

We already have some idea.

Deus ex machina

A few years ago, members of the self-alleged "Rationalist" community website LessWrong began discussing a idea experiment about an omnipotent, super-intelligent machine – with many of the qualities of a deity and something of the Old Attestation God'south vengeful nature.

It was called Roko's Basilisk. The full proposition is a complicated logic puzzle, but crudely put, information technology goes that when a benevolent super-intelligence emerges, it will want to do every bit much good every bit possible – and the before it comes into existence, the more good it will be able to do. So to encourage everyone to do everything possible to help to bring into existence, it will perpetually and retroactively torture those who don't – including anyone who and so much every bit learns of its potential being. (If this is the first you've heard of information technology: sad!)

An artificial super-intelligence could have some of the qualities of a deity (Credit: Getty Images)

Outlandish though it might seem, Roko's Basilisk caused quite a stir when it was first suggested on LessWrong – enough for discussion of it to exist banned past the site's creator. Predictably, that merely made the idea explode across the net – or at least the geekier parts of it – with references to the Basilisk popping upward everywhere from news sites to Doctor Who, despite protestations from some Rationalists that no-ane really took it seriously. Their instance was not helped by the fact that many Rationalists are strongly committed to other startling ideas about artificial intelligence, ranging from AIs that destroy the earth by accident to man-motorcar hybrids that would transcend all mortal limitations.

Such esoteric behavior have arisen throughout history, only the ease with which we tin now build a community effectually them is new. "We've always had new forms of religiosity, but we haven't always had enabling spaces for them," says Beth Singler, who studies the social, philosophical and religious implications of AI at the Academy of Cambridge. "Going out into a medieval town square and shouting out your unorthodox beliefs was going to get y'all labelled a heretic, not win converts to your cause."

The mechanism may exist new, simply the message isn't. The Basilisk argumentis in much the same spirit every bit Pascal's Wager. The 17th-Century French mathematician suggested non-believers should nonetheless become through the motions of religious observance, merely in example a vengeful God does plow out to exist. The thought of punishment as an imperative to cooperate is reminiscent of Norenzayan's "Big Gods". And arguments over ways to evade the Basilisk'southward gaze are every chip as convoluted as the medieval Scholastics' attempts to square man freedom with divine oversight.

Even the technological trappings aren't new. In 1954, Fredric Brown wrote a (very) short story called "Answer", in which a galaxy-spanning supercomputer is turned on and asked: is there a God? At present at that place is, comes the answer.

And some people, like AI entrepreneur Anthony Levandowski, recall their holy objective is to build a super-car that will one day reply just as Dark-brown's fictional machine did. Levandowski, who fabricated a fortune through cocky-driving cars, hit the headlines in 2017 when information technology became public knowledge that he had founded a church, Manner of the Future, dedicated to bringing most a peaceful transition to a world mostly run by super-intelligent machines. While his vision sounds more chivalrous than Roko's Basilisk, the church'south creed notwithstanding includes the ominous lines: "We believe it may be important for machines to see who is friendly to their cause and who is non. We plan on doing so past keeping track of who has done what (and for how long) to assist the peaceful and respectful transition."

"In that location are many ways people remember of God, and thousands of flavours of Christianity, Judaism, Islam," Levandowski told Wired. "Merely they're always looking at something that'southward not measurable or y'all tin't really see or control. This time it's dissimilar. This time you lot will be able to talk to God, literally, and know that it'south listening."

Reality bites

Levandowski is non alone. In his bestselling volume Homo Deus, Yuval Noah Harari argues that the foundations of modern civilisation are eroding in the face of an emergent religion he calls "dataism", which holds that by giving ourselves over to information flows, we can transcend our earthly concerns and ties. Other fledgling transhumanist religious movements focus on immortality – a new spin on the hope of eternal life. Still others ally themselves with older faiths, notably Mormonism.

A church service in Berlin uses Star Wars to engage the congregation (Credit: Getty Images)

Are these movements for real? Some groups are performing or "hacking" religion to win support for transhumanist ideas, says Singler. "Unreligions" seek to manipulate with the supposedly unpopular strictures or irrational doctrines of conventional religion, and and so might appeal to the irreligious. The Turing Church building, founded in 2011, has a range of cosmic tenets – "Nosotros will go to the stars and find Gods, build Gods, become Gods, and resurrect the dead" – but no hierarchy, rituals or proscribed activities and only 1 ethical saying: "Effort to deed with love and compassion toward other sentient beings."

Just as missionary religions know, what begins as a mere flirtation or idle curiosity – perhaps piqued by a resonant statement or appealing ceremony – tin can cease in a sincere search for truth.

The 2001 U.k. census found that Jediism, the fictional faith observed by the good guys in Star Wars, was the fourth largest faith: nearly 400,000 people had been inspired to claim it, initially by a tongue-in-cheek online campaign. Ten years afterward, it had dropped to seventh place, leading many to dismiss it as a prank. But as Singler notes, that is still an awful lot of people – and a lot longer than most viral campaigns endure.

Some branches of Jediism remain jokey, but others have themselves more than seriously: the Temple of the Jedi Order claims its members are "real people that alive or lived their lives according to the principles of Jediism" – inspired past the fiction, but based on the real-life philosophies that informed it.

With those sorts of numbers, Jediism "should" accept been recognised equally a religion in the Britain. Merely officials who obviously causeless it was not a 18-carat census answer did non record information technology as such. "A lot is measured against the Western Anglophone tradition of religion," says Singler. Scientology was barred from recognition every bit a religion for many years in the Britain because it did not have a Supreme Beingness – something that could also be said of Buddhism.

In fact, recognition is a complex issue worldwide, especially since that in that location is no widely accepted definition of religion even in academic circles. Communist Vietnam, for example, is officially atheist and often cited as one of the world'due south most irreligious countries – but sceptics say this is actually considering official surveys don't capture the huge proportion of the population who do folk faith. On the other hand, official recognition of Ásatrú, the Icelandic heathen religion, meant it was entitled to its share of a "faith tax"; equally a upshot, it is building the country's first infidel temple for nearly one,000 years.

Scepticism near practitioners' motives impedes many new movements from being recognised as genuine religions, whether by officialdom or by the public at large. But ultimately the question of sincerity is a red herring, Singler says: "Whenever someone tells you their worldview, you have to take them at face value". The acid test, as true for neopagans every bit for transhumanists, is whether people brand significant changes to their lives consequent with their stated faith.

And such changes are exactly what the founders of some new religious movements desire. Official condition is irrelevant if you can win thousands or even millions of followers to your cause.

A Russian church in Antarctica, where climate alter is playing out (Credit: Getty Images)

Consider the "Witnesses of Climatology", a fledgling "religion" invented to foster greater commitment to action on climate modify. After a decade spent working on engineering solutions to climate change, its founder Olya Irzak came to the determination that the real trouble lay non some much in finding technical solutions, simply in winning social back up for them. "What's a multi-generational social construct that organises people around shared morals?" she asks. "The stickiest is religion."

So three years ago, Irzak and some friends set nearly building i. They didn't see whatever need to bring God into it – Irzak was brought upward an atheist – only did start running regular "services", including introductions, a sermon eulogising the awesomeness of nature and education on aspects of environmentalism. Periodically they include rituals, particularly at traditional holidays. At Reverse Christmas, the Witnesses plant a tree rather than cutting one down; on Glacier Memorial Twenty-four hour period, they watch blocks of ice melt in the California dominicus.

As these examples advise, Witnesses of Climatology has a parodic feel to information technology – lite-heartedness helps novices get over any initial awkwardness – but Irzak'southward underlying intent is quite serious.

"We hope people get real value from this and are encouraged to work on climatic change," she says, rather than despairing nearly the state of the world. The congregation numbers a few hundred, but Irzak, as a skilful engineer, is committed to testing out ways to grow that number. Amidst other things, she is considering a Sun School to teach children ways of thinking well-nigh how complex systems work.

Recently, the Witnesses take been looking further afield, including to a ceremony conducted across the Middle East and cardinal Asia just before the spring equinox: purification by throwing something unwanted into a fire – a written wish, or an actual object – and and then jumping over it. Recast as an endeavour to rid the world of environmental ills, it proved a popular addition to the liturgy. This might have been expected, because it's been practised for thousands of years as function of Nowruz, the Iranian New Year – whose origins lie in function with the Zoroastrians.

Transhumanism, Jediism, the Witnesses of Climatology and the myriad of other new religious movements may never amount to much. But maybe the same could take been said for the small groups of believers who gathered around a sacred flame in aboriginal Iran, three millennia ago, and whose fledgling conventionalities grew into one of the largest, nearly powerful and enduring religions the world has ever seen – and which is nonetheless inspiring people today.

Maybe religions never do actually dice. Perhaps the religions that span the world today are less durable than we remember. And perhaps the next not bad faith is simply getting started.

--

Sumit Paul-Choudhury is a freelance writer and former editor-in-chief of New Scientist. He tweets @sumit .

Join more than one million Futurity fans by liking us on Facebook , or follow us on Twitter or Instagram .

If y'all liked this story, sign upwards for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter , chosen "The Essential List". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Hereafter, Culture, Capital, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

stockdillgolou1940.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20190801-tomorrows-gods-what-is-the-future-of-religion